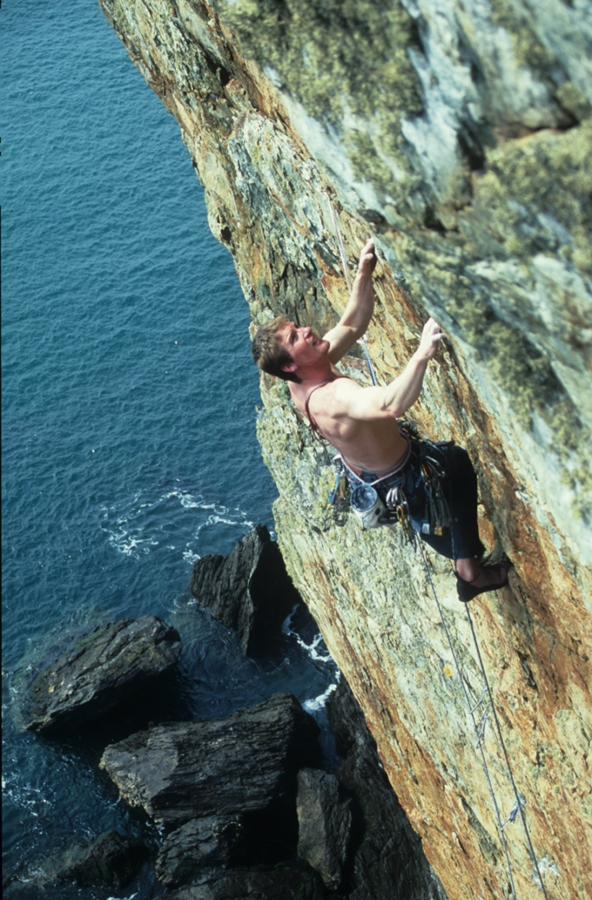

The Earth Died Screaming first ascent. Pic credit, Jethro Kiernan.

At the end of the first lockdown, when travel in Cymru was restricted – up the lanes from where I live, is Gideon Quarry. The imposing and well known Dinorwig Quarry, is to the east of Llanberis on the slopes of Elidir Fawr, Gideon sits on the west side of the valley, and feels secretive in comparison. Gideon is one of a series of holes burrowed into the hillside, collectively they are called the Quarries of Glyn Rhonwy. In the base, of Gideon, it’s vegetated and green, there are mature trees and bushes, and amongst this more wild environment, there are screeching kestrels, and ravens that turn clunking and clonking acrobatics, there are cheeky choughs with comedy crimson legs and bills.

Looking down from the natural bridge that separates The Land that God Forgot and Gideon, the left wall is an anomaly, the quarry is a slate quarry, but a section of the this wall is micro-granite. Given the travel restrictions, my friend Tim suggested I abseil and climb a, supposedly, (Tim just can’t help sandbagging his friends) good E4 called, The Bone People, and for once, Tim had not sandbagged me, it is a good climb. So good, in-fact, over a few days I climbed it several times. The E4 grade is a bit misleading, its almost fully bolted, (spaced!) so a few draws and a couple of small wires will do the job. Being outside and climbing after months of lockdown felt fantastic, but the weird feeling of not wanting to risk injuring myself because of everything going-on, was always in the back of my mind, which was a strange feeling for someone who has hardly taken a minute to consider personal risk in the past.

The weather throughout the whole of the lockdown period, like a really bad joke, had been warm, sunny and dry, but abseiling into the Bone People area, it was chilly and a little foreboding – enhanced by knowing there was no-way out, apart from climbing an E4, (or so I thought at the time) but, like many areas, once the initial plunge is taken, you desensitise and become familiar, and there is often an unknown and relatively easy, option. On this occasion the ‘easy’ option, if you can’t get out by climbing, is a boulder hop into the base of the quarry, where a careful scramble over, under, and through the piles of boulders, bits of metal, and brambles, leads to a scramble on the left side of the huge purple slabs, (as long as it’s not raining!) and to make this even more straight forward, there are some in-situ ropes to pull-on, if someone hadn’t pulled them up (definitely needed if raining).

George Smith. The Man, the legend, my (annoying) hero, on the first ascent of his problem, The Whale Shark, Gideon Quarry. I would include the grade, but that will make me complicit with his lies!

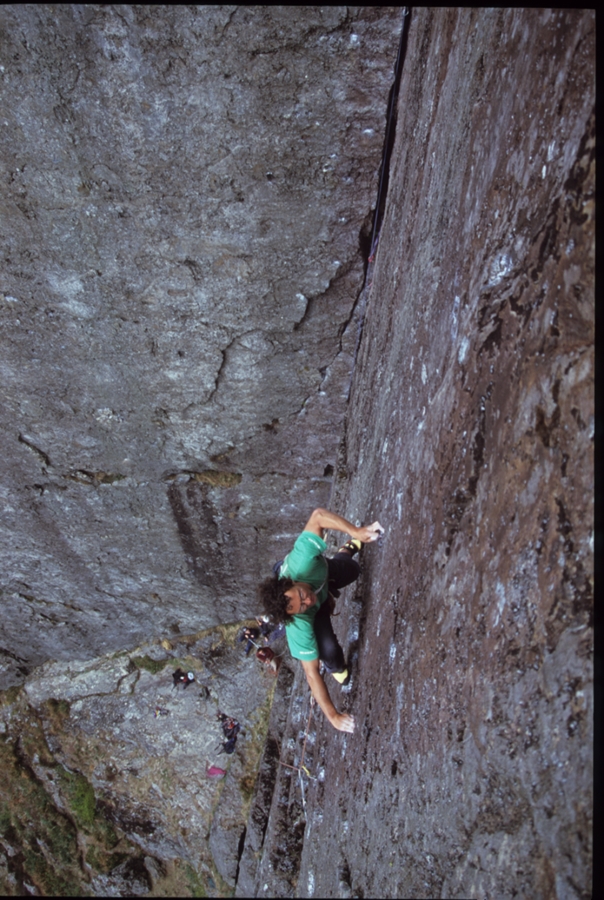

Now, a person that has hardly had a mentioned on this blog and, in my opinion, has gotten away lightly, is Big George Smith. George is a bit of a hero. Admittedly, he’s a fucking annoying hero, but, hero nonetheless! George has climbed many new routes and boulder problems in well-known, and esoteric areas of north Wales; quirky, weird, thrutchy, overhanging, quality, crazy, funky – beautiful climbs, hundreds of the buggers, some are even good, but the one thing they all have in common, the one thing each, and every single one of them share, they are all undergraded. And every time I’ve been shut down on a George climb, (and take it from me, its often) all I can hear is his annoying laugh! I love George, but his bloody natural talent is so annoying, and I love/hate the climbs he gives the grade E5 even more! His legs are so big and long, he bridges everything, and if he can’t bridge, he knee-bars, and when he can’t knee-bar, he starts all of that bloody ridiculous backhand, underling nonsense, I mean, that’s not proper climbing! The Ragged Runnel, E5 6a my arse. The Undercling, E5 6b my arse, Chosstakovich, E5 6a, in someone’s wildest dreams, not mine! I’ve lost count on George routes I’ve failed, what a big lovable sandbagging wanker!

George and that under the radar, understated, Martin Crook were skulking around the quarries, and it turned out, George was working a new boulder problem in the base of Gideon. In typical Smith style, it looked fantastic, he just had an eye, a very annoying eye, but an eye for a great line, and with my new found interest in Gideon, we were bumping into each other frequently. One day George and I sat on the opposite side on the Bone People Wall looking around. I’m not sure if it was George or me, who pointed out a big, and quite obvious, overhanging corner/groove to the left of The Bone People and a climb called Synthetic Life. Because of lockdown restrictions, I had, by that time, checked out the other climbs on the wall, one of which is Synthetic Life, a long sport route first climbed by Pete Harrison and given the grade of 7a+. It’s a fantastic climb, but I think Pete must have been taking lessons from George when he graded this one, as (in my bumbly opinion) it’s harder than 7a+, and in the middle feels more like an E6. George and I sat two metres apart, on a large lump of slate, looking over at the wall while picking out unclimbed lines, but there was one that stood-out more than the others. Knowing that George was into his bouldering at the moment, I said I might throw a rope down this line to see what it was about, and a few days later that’s what I did.

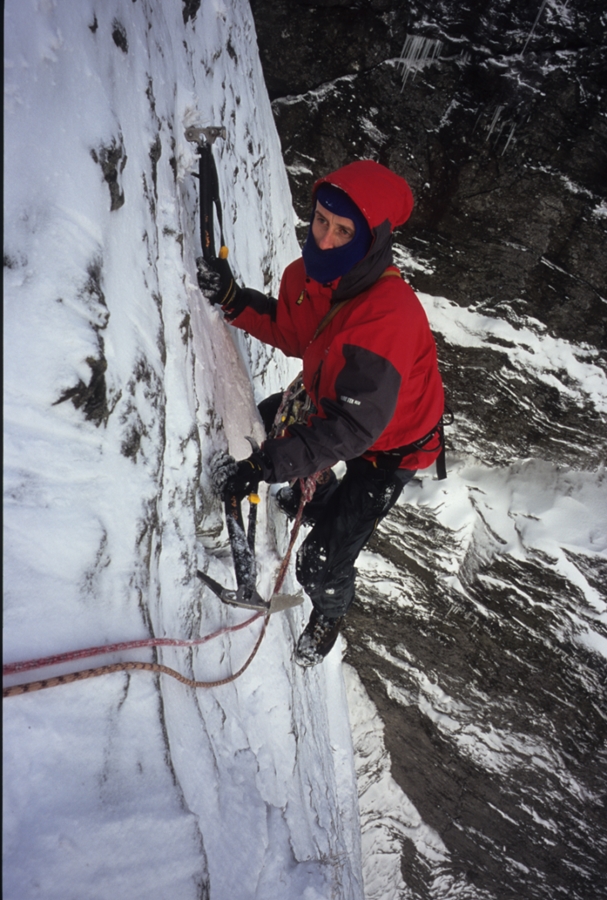

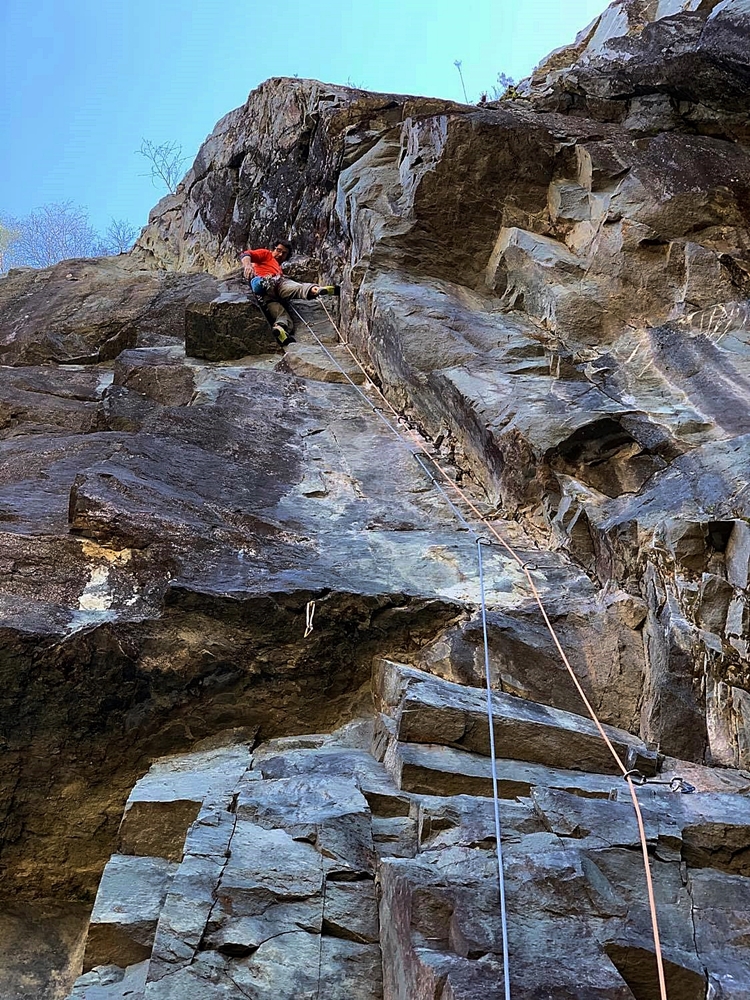

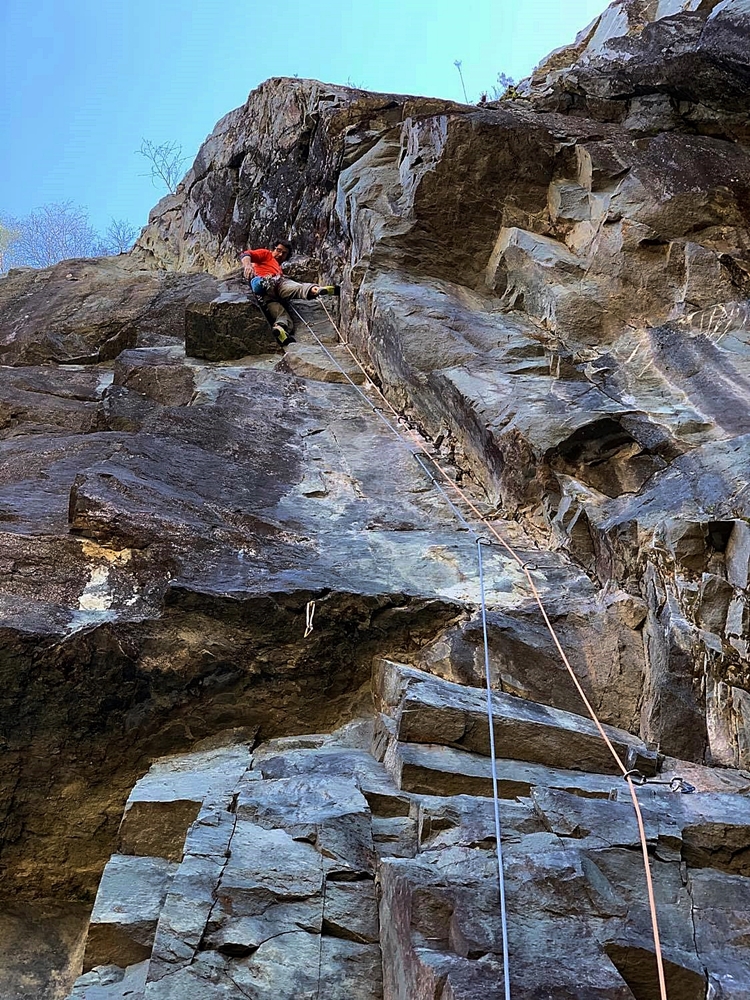

Myself hanging in the middle of the unclimbed line. Pic credit, TPM.

I stood on the small ledge above the groove, arranged rope protectors, and for the first time, abseiled over…. Wow, the top of the groove was a massive keyed in block, and on the climbers right of the block, was an overhanging, hand-sized crack, running for about five metres. Below were some, smaller, keyed-in blocks with cracks and spikes, and beneath, a three-dimensional corner with a perfect fingerlock crack. It looked like there would be a fair bit of cleaning, especially in the lower crack because it looked really filthy, but I was sure it would go with a bit of work.

The next day I went to Gideon, and abseiled-in, but this time, I placed several pieces of gear, including a couple of pegs, so I could remain close to the rock. I brushed and scraped and pulled and brushed and scraped. And when I reached a large ledge near the quarry base, I began to jumar back up to get an idea of the climbing. Overhanging fingerlocking with smeary feet, into a weird 3-D chimney, followed by the long jamming crack, and a steep pull to finish back on the ledge. I abseiled again, digging mud, clearing dirt, chalking the crack, before jumaring and doing more of the same. When I stood in the grass at the top, I checked the time – eight hours on the rope, no wonder my back was hurting.

Sometime later, travel restrictions lifted, so I talked TPM into coming over to bolt the top slab; climbing the slab would be more enjoyable than pulling up a fixed rope. I also asked him to fix a double bolt abseil/belay anchor at the ledge above the main pitch. He bolted the slab quickly, but when he stood on the belay ledge about to drill, he discovered someone, (Pete Harrison I later found out) had already drilled, and placed two bolts leaving them without hangers (thanks Pete 🙂 ). I abseiled down, brushing and cleaning, and then on a top rope, climbed back out, brushing and chalking the muddy finger crack along the way. At the top of the fingercrack, there were a couple of difficult moves entering the weird chimney section, but above this, the spikes and the long hand-jam crack were fantastic. The rock boomed a little, because, as I originally thought, it was a massive detached, triangular block, but it was so big and had been in place for millions of years, it wasn’t going anywhere. I even jumped up and down on it a few times. Safe as houses, here for another million years! The continuation of the groove was full of loose blocks, so I climbed the final overhanging wall to the right and pulled onto the ledge.

“Game on.” I said to TPM.

“Aye.” He enthusiastically said back.

We both looked at all of the blocks in the top of the groove,

“What do you think I should do with them.”

“Shift em.”

So I cleared the top of the groove, exposing the lower groove to run-off when it rained, but certainly making it safer. Mick then climbed Synthetic Life and afterwards, we stood at the top and arranged to come back to climb the new route.

*

“AH, bugger, there’s a problem.” It was a few days later when I shouted up to Mick, who was about to abseil to the small ledge at the top of the groove.

“What’s that then?”

“The top of the climb has disappeared!”

“The bit you cleaned, right at the top?”

“No, the top third of the climb, the whole of the block with the jamming crack, it’s gone, I can see it in the bottom of the quarry.”

“What’s left?”

“Nothing that I’m going to climb today, it’s a smooth muddy groove.”

Slightly distraught that my new, brilliant jamming route had been snatched from me, I belayed Mick on The Bridge Across Forever, a brilliant climb put up by Chris Dale and Trevor Hodgson, both great climbers and big characters, and both, saddly dead, having contracted cancer.

Sometime later that week, I returned by myself to Gideon, armed with several brushes, wishing I had a portable power washer. At the end of the day, I stood coiling ropes in what was becoming the familiar grass, while watching the sun set over the distant sea. I had beaten my previous time hanging on a rope by two hours – ten hours of brushing and digging mud from cracks with a nutkey.

When the pandemic restrictions stopped, Mick and I began to venture further afield, and my Gideon obsession was almost put on the back burner, due in part by the rain, but I spent the occasional day by myself, sliding into the depths, brushing, cleaning and digging with a nutkey. No matter how much mud I dug from that bloody crack, there was always more, and every time I stuffed fingers into perfect locks, they always came out wet and covered in mud. The massive block that now lay in the base of the quarry had exposed an open and slabby groove, it was plastered in a skin of mud. My initial vision for the climb had been for it to be climbed on gear, with maybe one peg in the middle section to take the sting from a run-out, but the big block’s demise had me wondering if this was now feasible, because the walls were compact. Two smaller, keyed-in blocks, in what would be the middle of the pitch, remained. I really wanted these blocks to stay, as the climbing beneath them was pumpy and difficult. The blocks would give something to aim; good holds, good gear and good feet placements around them. But, knowing what had happened to the massive block, I began to treat them with suspicion, somethin akin to a Big George E5. I jumared up after a lap of cleaning, and at the base of the lower block, I could see it was completely separated, and like the massive block, it was held in place, only by time, mud and its own weight. The lower block also held the block above. Gingerly, I passed it, giving it a bit of a thump. It moved a bit, but maybe it’d be ok, it was quite big and it took a pull!

Later that night I spoke to Mick,

“Shift em.”

“But I need them.” I pleaded, knowing he was right, but also knowing it would reveal more, smooth, mud-covered rock, and less chance for gear.

Another day, another slide into Gideon, but this time, not only armed with brushes, I had loaned a crowbar from Mick. I hung by myself; just me, several brushes, a crowbar and two blocks. After the massive block incident, I considered these two as small, but in reality, they were fridge size, admittedly, a UK fridge, not one of those USA things, but still… I hung on a single rope, and the more I considered what I wanted to do, the more concerned I became. I imagined a whole host of scenarios; the blocks toppling, hitting me, ripping off limbs, cutting the rope, with me eventually laying down there in the base of the quarry, alongside the massive block, only to be discovered by George and Crooky as they ferreted around, inspecting the massive block for problems, wondering how they had misses it in the past, and even more strange, where did that chalk on it come from!

I inserted the bar into a crack and levered, but nothing happened. I tried again, and still nothing happened. Well, I thought, good, they can stay. Then I remembered the crack at the base of the lowest block, so I placed the thin bit of the bar into the crack and pushed, and without any effort, the whole thing moved with a clunk. Slowly, I reduced the pressure on the bar, and eventually breathed. “Fuck.” OK, they had to go. I jumared, pulled all of the rope and coiled it around my foot, propped myself as far away as possible, and levered. The bottom block clunked, and slid, almost as easy as it is to say, whatthefuckamIdoinghere… The top block somehow remained in place, so after moving up, I stuck the bar into its side and gave it a little pull, and off it went to join the other two. More smooth rock with less holds, more mud, less gear placements. I began brushing feeling a tad dispondent!

As the weather became more unsettled, I had another day, maybe two, brushing and cleaning and digging out mud from the crack. One day, the clouds were building as I slid over the edge, and by midday, the sky turned dark, and then almost black. A flash of lightening, and a crazy booming echoed around the quarry. The trees bent double, and the ravens honked and flew to a ledge. Where the two blocks had been, was now a small ledge, it was about half way up the pitch and covered in mud. I jugged and stood on the ledge. Boom, another explosion. Rocks rattled down the cliffs. The sky opened then, and the rain and hail began, and it was heavy, like something you would expect in the Amazon Rainforest. I stood on my little ledge looking out and a waterfall arced over the top of me laughing, imagining someone walking to the natural bridge, and looking into the quarry, to see me stood on my own, hanging from a rope in a maelstrom and laughing. The storm passed over, so I continued to clean, but instead of brushing, I now grabbed handfuls of sloppy mud.

Winter and another lockdown stopped my cleaning, but in the spring, I returned to Gideon and was surprised by how dry and clean the climb was, my efforts from last year, and the winter rain, had done the job. The fingerlock crack was of course wet and muddy, so I dug more mud from it.

For the first time since starting this stupid thing, I had a wobble about it being a trad route. The climbing was going to be tough in this bottom section, and the thought of fighting the pump, placing gear and climbing on with muddy fingers made me think I should ask Mick to bolt it. Bolting it would at least mean it was the same as the three climbs to its right, and it may also get a few ascents, but before making a final decision, I’d ask Mick to have a toppy and see what he thought. Apart from one bit in the middle, the gear was generally good, and I’d feel a bit disappointed, and truth be told, embarrassed to bolt a line with such good gear. I suppose if it was bolted, others would do it, but to me, this always seems a poor reason to bolt a line that was first climbed as trad, or a line that will go on trad gear, it robs the (fewer) people who may want a more intense and challenging experience, and for what, a bit of convenience? Its so easy and tempting to make something more appealing and popular, but I’m not sure this is always a good enough reason to make it more accessable and lose something different and special, something that a bit of trouble and effort makes more worthwhile and memorable?

A week later, Mick came over on a miserable day, and we both climbed the line on a top-rope. At the end of the day, we decided it should remain a trad climb, there was enough gear and it climbed really well.

I had one more day by myself cleaning and chalking the bottom crack, (the ninth, over a twelve month period) before taking out the wires and pegs. I was going to leave one peg in to make the run-out in the middle less, but I imagined someone abseiling in, attaching a long sling to it, and turning my climb into an easy ride, so I took the peg out! Twelve months had passed since I had started on this thing, twelve months, bloody hell, and what a twelve months we have all had! I couldnt believe it was (hopefully) almost over.

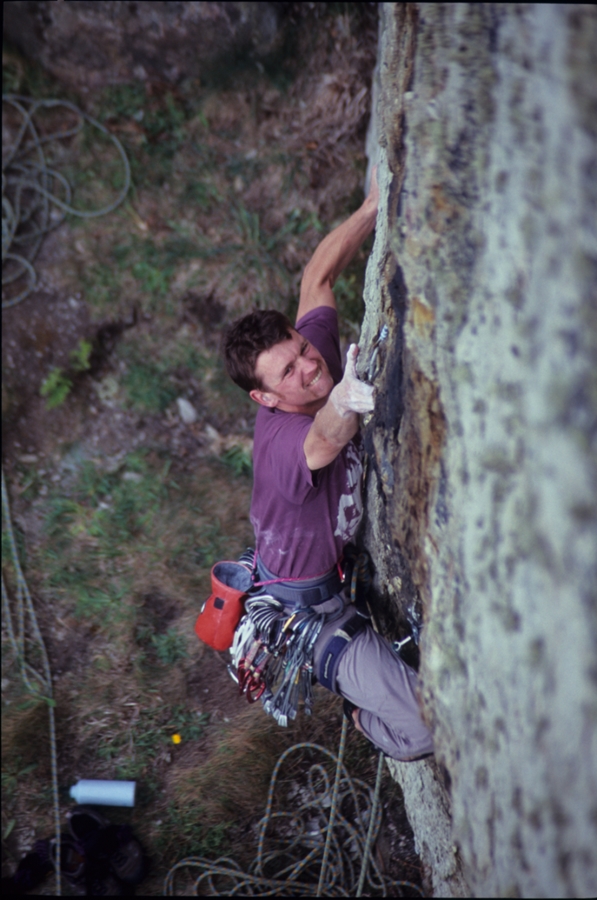

A couple of days later, Mick and I returned and Jethro Kiernan came along to take pics. After a warm-up, I led the main pitch and Mick seconded it before leading the first ascent of the top pitch, which is about 4c sport, he didn’t appear to struggle too much! We were going to call it Bone Machine after a Tom Waites album, but because it was Earth Day, we eventually decided on, The Earth Died Screaming, which is the first track on Bone Machine, and considering everything going on, seemed appropriate.

The fingerlock crack. Pic credit, Jethro Kiernan.

The crux, moving from the top of the crack and into the chimney. Pic Credit, Jethro Kiernan.

This is just after the crux, in the chimney. Credit, TPM.

Starting the run-out… Pic credit, Jethro Kiernan

Myself grabbing the ledge, that once held the two smaller blocks, it’s the same ledge that I stood on while a waterfall arced over the top of the crag. This is the run-out bit, but the gear is amazing. Pic credit, Jethro Kiernan.

Almost there… Pic credit, TPM.

TPM seconding the main pitch. This is the run-out bit, aiming for the little ledge.

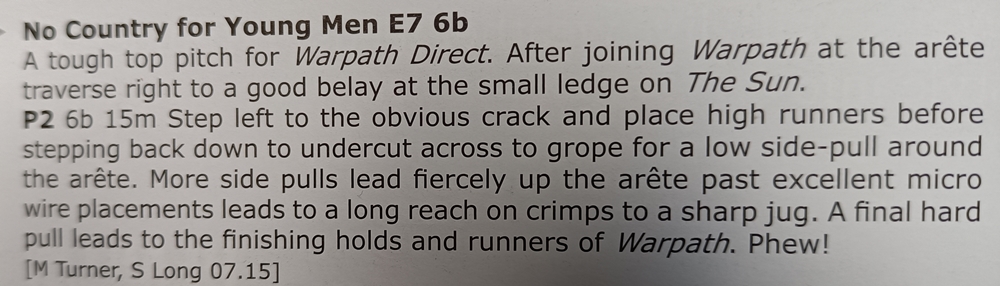

The Earth Died Screaming. E6 6b 50m. Nick Bullock, Mick Lovatt. 22/4/21

The climb is two pitches, but the first pitch is, THE pitch; an overhanging groove that remains dry in wet weather, although the fingerlock crack at the start suffers a little from seepage and will be best after a dry period. The main pitch is sustained, technical, varied, and well protected, apart from a bit of a run-out in the middle section, which raises the grade from E5 to E6. Take a good selection of wallnuts, half-nuts, off-sets, microcams and cams (up to a gold Dragon). The second pitch is a clean, 4c (sport) slab that was bolted so people can climb out, much more enjoyable than pulling out on a fixed rope.

The climb is the overhanging groove to the climbers left of Synthetic Life. The approach is from a Silver Birch near the top of the scree that can be used as an anchor to carefully walk down the scree to another birch tree at the top of the slab. Abseil down the slab from the tree to a good ledge (double bolt anchor). Either fix an abseil rope from the anchor or rig it so you can pull your ropes. A forty metre abseil reaches a good ledge beneath the climb. A fixed belay is in place, so, if needed, a short abseil can be made into the base of the quarry where a scramble on the left of the slabs (ropes sometimes in place) to a tree, or a crawl through the tunnel system (right) leading to another tunnel and a scramble from Filmset Quarry, will provide escape.

Pitch 1. 35m

Climb easily from the belay until beneath an overhanging corner with a fine looking fingerlock crack. Climb to the top of the crack (great gear). Exiting the crack, and entering the wide, bottomless chimney is the crux. At the top of the chimney, place bomber gear before entering the slabby groove (bold). At the top of the groove, a large ledge is reached (small, not brilliant cams, and a small wire are just enough to steady the nerve). A thought provoking move left from the ledge leads to steady climbing and good gear. After a few moves up, a step back right into the top of the corner before moving right across the overhanging wall leading to an exit onto the belay ledge.

Pitch 2. 15m

Climb the slab. Belay from the tree at the top of the slab.